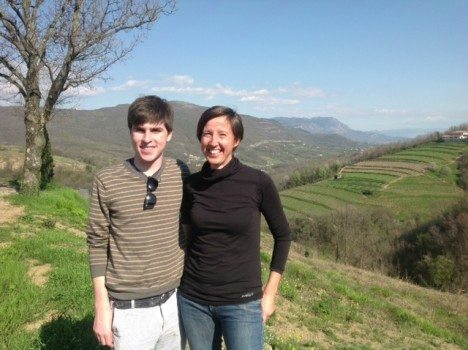

Driving ever-so-slowly on the twisting road that meanders back and forth across the Slovenian/Italian border on the approach to Josko Gravner’s home is advisable; it is the only reliable way to catch a landmark glimpse of the few spent giant amphoras serving as signposts to the home that Gravner’s father raised him in and that Josko still lives and raises his own wines in. My son and tasting partner Alex made the non-trivial commitment to planes, trains, and automobiles starting out in Copenhagen, and me from Boston, to meet up in these drop-dead gorgeous rolling hills that are Friuli-Venezia Giulia’s ground zero for overly expressive wines made from local indigenous grapes. This small stretch of road was the final lap and we would not let Josko Gravner off the hook until we understood more about what made his compelling orange wines different from all others.

Driving ever-so-slowly on the twisting road that meanders back and forth across the Slovenian/Italian border on the approach to Josko Gravner’s home is advisable; it is the only reliable way to catch a landmark glimpse of the few spent giant amphoras serving as signposts to the home that Gravner’s father raised him in and that Josko still lives and raises his own wines in. My son and tasting partner Alex made the non-trivial commitment to planes, trains, and automobiles starting out in Copenhagen, and me from Boston, to meet up in these drop-dead gorgeous rolling hills that are Friuli-Venezia Giulia’s ground zero for overly expressive wines made from local indigenous grapes. This small stretch of road was the final lap and we would not let Josko Gravner off the hook until we understood more about what made his compelling orange wines different from all others.

So, it was important to me that we made friends, and that part came together nicely.

To get there without any Italian, we leaned on Gravner’s daughter Jana, who was as charming and smiling an interpretor as you could ever ask for. Truth be told, Gravner wines are so unique that Jana can not drink any other wine made anywhere in the world, not even in Italy, besides her father’s. They simply don’t work for her, and this might be the only instance where I could appreciate that kind of position. We made friends with Jana, too.

To get there without any Italian, we leaned on Gravner’s daughter Jana, who was as charming and smiling an interpretor as you could ever ask for. Truth be told, Gravner wines are so unique that Jana can not drink any other wine made anywhere in the world, not even in Italy, besides her father’s. They simply don’t work for her, and this might be the only instance where I could appreciate that kind of position. We made friends with Jana, too.

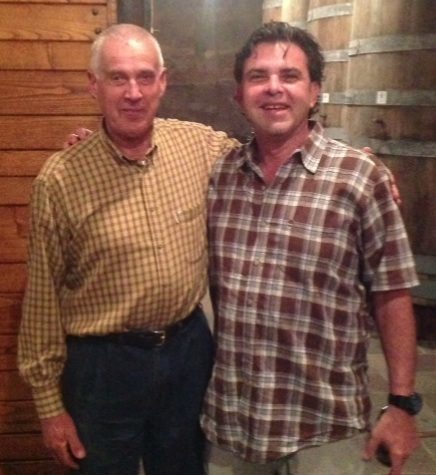

Wait, stop right here. Alex and I, father and son, both astounded and taken by the sheer power, character, and complexity of these one-of-a-kind Gravner wines we were drinking all week across Northeast Italy and now here we were with father and daughter, shepherds of these wines, walking vineyards and cellars with Josko leading the way, thief in hand. I have written hundreds of stories here at WineZag about impressive world-class wines, but I can assure you that while you may or may not like the unique profiles of wines made by Josko Gravner, to me they stand as the most uniquely riveting white wines that I have ever put to my lips (happy to leave the tasting notes to the very fine and pointed WineAnorak’s vertical Gravner tasting wrap up). Spending some time with Josko, a man of quiet and purposeful strength with an unyielding vision to abide by history and nature for producing what’s right, was turning out to be anything but trivial.

Early on I thought we might lose Josko to the vineyard until I probed directly, “We drank your wine side by side last night with a Radikon Ribolla Gialla and I was wondering if you could explain to us what about the winemaking leads to such distinctively different styles of “orange” wines?” Radikon is made literally 100 yards down the road, yet the two winemakers are separated by 1000 kilometers of sytlistic differentiation. Radikon is only one example; I could have mentioned Movia, Primosic or others as further examples. The question stopped Gravner in his tracks and refocused the conversation. With a thoughtful but challenging smile he quietly answered with a question of his own, “Which one do you prefer?” It was no stretch letting Josko know that I preferred the Gravner style for their glacial edges and smoothness, seamless mouthfeel, pure flavors, liveliness, tight showiness, class, and complexity. Actually, I can not think of any other wine in the world like it. The Radikon was no match with its pronounced oxidation and I just wanted to understand why.

Jasko classifies his wines as “amber, I do not make orange wines. Many orange wines are overly oxidized. My wines that I make are amber.” He pointed out that amber contains organic matter while orange is a color. “My wines are living” things that require sulphur in the wine making process to protect them. Without sulphur, Josko explained without mentioning any other producer by name, you can not keep the wine alive and you will experience annoying oxidative character that is not about the fruit. Gravner was quick to hang his hat on his minimal but regular applications of just the right amount of sulphur as the key to this bifurcation of orange wine styles, rendering his amber and the rest orange.

Certainly, there must be more.

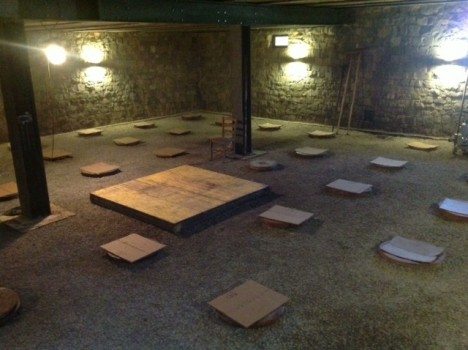

Gravner does not believe in technology in winemaking. He has eliminated all refrigeration and steel from the cellar except for one small destemmer. “Technology runs its course in ten years and then it needs to be updated and changed,” Gravner says “unlike the process I use that has worked for more than 1,000 years.” And of course, Georgian amphoras large enough to fit almost two men in, buried in the ground below his house and working cellar holding grapes for just less than one year during full skin contact maceration, contribute to the formula. Only then, with the skin providing the deep amber colors the vineyard and vintage are willing to impart, does the wine move into wood upstairs. These wines sit around the cellar in various stages for six years until they are released. We joked how this is a perfect strategy for “not” making a lot of money in the wine business.

It’s quite eerie walking into the cellar of macerating grapes and seeing nothing:

Tasting from amphora proved the cellar was anything but empty as natural yeasts did their work:

It all starts in the vineyards for Gravner, and we noted the man-made ponds in his old and brand new vineyard. Attracting insects and birds keeps the balance of nature for the soil and total vineyard environment. Gravner has made his last vintage of Breg, a blend of Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Pinot Grigio, and Riesling. All the vines were pulled to make room for more Ribolla Gialla, the true local varietal. As for the non indigenous varieties; the terroir should not support them. He has also ceased production of red wines made primarily from Merlot, which is honestly a loss to the wine drinking world. Again, the land and its ancient connection with the vines drive a natural order for Josko Gravner.

We had the chance to taste Ribolla back to the 1998 vintage with the Gravners. These wines are seamless, powerfully elegant, structured, filled with herbs, and always austere and gracious like ice age glaciers. The chance for Alex and I to meet and drink with Josko and Jana Gravner was a pinnacle and privilege in my life of wine; a moment I will never forget.

During dinner at The Marrow in New York last night, over a glass of Movia, my friend asked my what has me so taken about Josko Gravner and his wines. It was a powerful question and the answer goes beyond the drinking experience. It is more about a man that has take over his family’s wine enterprise that began at the start of the 20th century, pursued wines that he liked without regard for the marketplace, defied common practice, spurned technology, introduced ancient amphora, turned to the balance of nature for predictable results, and from his small hillside perch and humble home in the far reaches of Northern Italy commanded the attention of a global market simply by pursuing what he thought was right and ended up with wines that nobody else has come close to replicating. Alex witnessed all of this by my side first hand, with great understanding and approval. What else could a wine loving father ask for?

There is an orange wine rage going on. This week in NYC I spotted orange wines on three different by-the-glass lists in restaurants and bars. In one bar, the Lambs Club, a glass of Gravner’s amber wine sold for $68. That’s the difference between orange and amber. No worries, though, you can buy a bottle of Gravner Ribolla for about $75. Defy the rage, drink amber by the bottle!