It’s a controversy I won’t take sides with and instead hope to convince you of its senselessness.

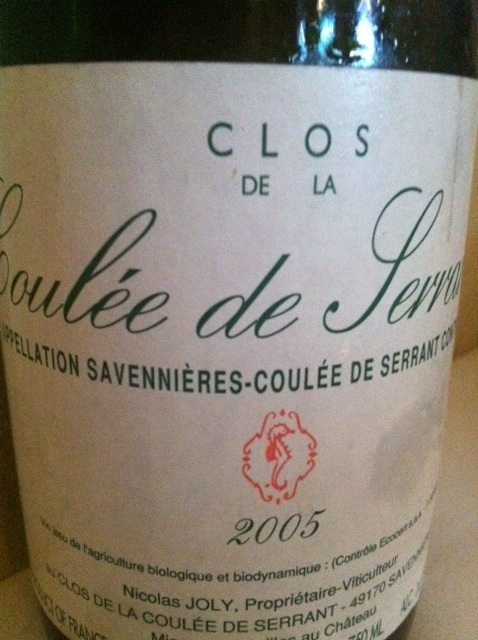

Never mind the plethora of world class, fairly priced, old world wines anchoring my enthusiasm for the Loire Valley. Instead, let’s focus on magicians like Foucalt, Huet, and Joly that are flooding my deepening vortex of Loire fanaticism with mystery and passion. On a recent evening that reminded me why I obsess enthusiastically about wine, I shared 2005 vintage examples from two of these iconic winemakers with an appreciative friend and colleague; Foucalt’s ($65-75 *****) Clos Rougeard Saumur Champigny and the ($45-80 ****) Joly Coulée de Serrant Savenniéres finishing with Italy’s ($25 375 ml ****1/2) Carlo Hauner Malvasia Delle Lipari from its namesake volcanic island off of the northern coast of Sicily. It was that kind of evening; when dreamy wines envelope tasters in a furry blanket of alluring pleasure.

Never mind the plethora of world class, fairly priced, old world wines anchoring my enthusiasm for the Loire Valley. Instead, let’s focus on magicians like Foucalt, Huet, and Joly that are flooding my deepening vortex of Loire fanaticism with mystery and passion. On a recent evening that reminded me why I obsess enthusiastically about wine, I shared 2005 vintage examples from two of these iconic winemakers with an appreciative friend and colleague; Foucalt’s ($65-75 *****) Clos Rougeard Saumur Champigny and the ($45-80 ****) Joly Coulée de Serrant Savenniéres finishing with Italy’s ($25 375 ml ****1/2) Carlo Hauner Malvasia Delle Lipari from its namesake volcanic island off of the northern coast of Sicily. It was that kind of evening; when dreamy wines envelope tasters in a furry blanket of alluring pleasure.

I won’t add to my already infatuatory remarks about this vintage of Clos Rougeard, but once again it showed off in heart stopping fashion. I pulled the wine from my cellar to pair with the inventive French country fare at a favorite Cambridge restaurant and since the 2005 Joly Coulée de Serrant sits on their list for $89, it just made sense pairing up this controversial Chenin Blanc with the Foucalt brothers’ same-vintage Cabernet Franc for an indulgent evening of Loire wine. Every time I taste Joly’s Chenins I understand, and quickly dismiss, the ongoing controversy surrounding these wines.

For a substantial insight into the pioneering eccentricity and single mindedness of the winemaker, and now his daughter Virginie, be sure to check out the excellent historical background piece on the controversy and vineyards of Nicolas Joly and specifically the Clos de la Coulée de Serrant at the Winedoctor. What is inarguable, though, is that this seven hectare red schist vineyard site planted to Chenin Blanc iconically sits on a list of the greatest patches of land found anywhere in the world for cultivating grapes and making wine. Joly was an early biodynamic thinker, often accused of taking things to extraordinary limits of natural and biodynamic obedience, creating wines that are more than they should be, and maybe not what they are meant to be. Accusations of oxidation, bottle variation, and over the top Chenin ripeness abound. Joly disagrees vehemently and insists that Chenin is best harvested at full ripeness, touched by botrytis, producing a color that looks like, but isn’t, oxidation. I don’t really care, and let me tell you why.

For a substantial insight into the pioneering eccentricity and single mindedness of the winemaker, and now his daughter Virginie, be sure to check out the excellent historical background piece on the controversy and vineyards of Nicolas Joly and specifically the Clos de la Coulée de Serrant at the Winedoctor. What is inarguable, though, is that this seven hectare red schist vineyard site planted to Chenin Blanc iconically sits on a list of the greatest patches of land found anywhere in the world for cultivating grapes and making wine. Joly was an early biodynamic thinker, often accused of taking things to extraordinary limits of natural and biodynamic obedience, creating wines that are more than they should be, and maybe not what they are meant to be. Accusations of oxidation, bottle variation, and over the top Chenin ripeness abound. Joly disagrees vehemently and insists that Chenin is best harvested at full ripeness, touched by botrytis, producing a color that looks like, but isn’t, oxidation. I don’t really care, and let me tell you why.

Each time I drink Coulée de Serrant, from any vintage, I am overwhelmed by its exuberant statement, wild nose, rich mouthfeel, fruit character, and exotic flavors–easily convinced that I am drinking a wine impossible to find or make any place else or in any other fashion. Joly is taking what the earth naturally gives him, and applies his uber-natural philosophy to produce a wine of singularly compelling style. The enigmatic wine’s profile might not appeal to everyone, but it is profound in its own right and it is simply wrong to dismiss the legitimacy of the wine when it creates such a powerfully unique and enjoyable representation of Chenin Blanc. The controversy is as useless here as it is in any disagreement over a specific wine by two different tasters with personal palate orientations. I say, “to each his own and let’s cork the argument.”

The 2005 Coulée de Serrant shows a familiar deep golden color. Its nose has touches of mushroom, honey, and caramelized hazelnuts, with a melange of fruity aromatics incorporating pear, ripe apple, and peach. As overly impressive is the weight of the wine in your mouth. It offers a richness and voluptuousness that is simply not what you think of with Chenin Blanc. And it all marries with almost enough acidity, actually asking for more of that, and then rounds out a long finish with a hint of lime citrus. The first glass conjured up kindred thoughts of the magic Zind Humbrecht manufactures with Pinot Gris, Riesling and Gewurtztraminer from some of Alsace’s most heralded sites; never to be mistaken for these Zind Humbrecht produced varieties, but similar in richness and pronounced nuances that are hard to imagine until you taste wines from these producers. The wine made us smile, sit back in our seats, and luxuriate.

The evening wore on and we reveled in the Clos Rougeard, returning to our glasses of Chenin Blanc occasionally. We poured the sweet Malvasia, and continued to return to the remaining Chenin in our original glassware. Sadly, the wine wore out. It lost its vibrancy and any form of crisp brightness that it showed two hours earlier. It stumbled haplessly to the finish line. On his website, Joly insists:

Once opened, wines made in this way continue to improve – and are in no way oxydized.

To be sure that the color is not oxydation you can make the test yourself by tasting each day a glass over several days without putting the bottle in the fridge just recork. You will see the wine improving the first days even sometimes over more than a week. If the wine would be oxydized it would be undrinkable.

Not so with this particular bottle of the 2005. Maybe it’s bottle variation and just maybe it is oxidation. But none of that matters, and that is why the controversy is useless. For an hour we enjoyed one of the most interesting bottles of Chenin Blanc you could ever imagine pouring. It was surreal and held our total fascination. I loved drinking it, and would not have traded that experience for anything else.

Maybe the critics are indeed correct claiming the wines are too high in alcohol, flawed and technically unsound. But, maybe Joly is on point with his delayed harvesting, fanatic biodynamic farming, and eccentric vinification methods. Who really cares when you can enjoy, sometimes for just one hour, the most unique Chenin Blanc available in the world.